An Alternative Approach to Creativity and Music Literacy with Real-Time Iconic Graphic Notation

Richard Edwards, Ohio Wesleyan University

Abstract

This article shares the pedagogical approach, assessment results, and reflections from a composition project with 5th grade general music students using a new method for developing music literacy based on a form of iconic graphic notation (IGN) that can simultaneously combine simple creative tasks, note writing, and singing activities in real time at the tempo of a live musical performance. Also presented is a rationale for why an alternative approach to teaching music literacy and creative musicianship might have merit based on three principles of music learning: the inherent potential for creative musicianship in all people, a natural sequence of learning that builds upon active experience, and the value of finding a balance between structure and creative options in the learning process. Students quickly grasped the mechanics of the IGN method within minutes and, by the end of the project, all of the students involved created an original melody within the context of the IGN structure. Potential benefits of the IGN method include real time feedback supporting aural awareness and music literacy, easily produced individual assessment opportunities, and fostering constructivist learning activities capable of enabling creative tasks with students of different music ability levels at the same time.

An Alternative Approach To Creativity and Music Literacy

With Real Time Iconic Graphic Notation

A fundamental premise of this article is that everyone is capable of performing and creating original musical ideas at any stage of their musical development. While genetic traits may vary the facility with which one learns to be musical (Peretz, 2007; 2009), the capacity to become a musically creative individual involves the acquisition of discernable musical experiences to form a knowledge bank of musical information that can be drawn upon whenever opportunities to appreciate, perform, or create music arise. As Gordon has explained, “Your level of music aptitude and the extent of your education and experience determines the quality of meaning you are able to offer to music at any given time” (2003, p. 4).

The acquisition and development of linguistic knowledge has often been interpreted similarly to the acquisition and development of musical knowledge (Gordon, 1997; Azzara & Grunow, 2006) and some research suggests that there may be a neuroscientific basis for these reported commonalities (Levitin & Menon, 2003; Koelsch et al., 2002; Patel, 2007; Saffran, 2003; Zattorre, 2005). Just as all children gain experience observing and speaking the words around them en route to comprehending their local linguistic vernacular until they are able to make patterns of words that communicate original verbal ideas, so too are all children equipped to gain experience observing and performing the musical sounds around them en route to comprehending their local musical vernacular until they are able to make patterns of pitches and rhythms that communicate original musical ideas.

The rationale supporting the inherent human potential of developing musicality also relates to the comprehensive recommendations of Wiggins and Espeland for fostering and supporting creative learning processes. They present a three-part platform to summarize the process of meaningful creative learning based on a social constructivist and phenomenological approach, a strong belief in the creative musical potential of young people, and a value for creative educational opportunities that are culturally embedded, holistic, and authentic in nature. (2013, p. 356)

The mental preparation for understanding the tonal patterns in a student’s mind is an important part of the formative process leading to the production of musical material during creative activities (Azzara & Grunow, 2006; Gordon, 2003; Hickey, 1996; Kratus, 1990; Wiggins, 1996). In addition, creative learning experiences for students may also be facilitated by using non-traditional forms of music notation (e.g., graphic notation, idiosyncratic symbols, or invented notations) to cultivate the musical imagination of children at their existing level of cognitive development (Barrett, 2004; Strand, 2011). Non-traditional music notation systems such as graphic notation and student invented notation offer a valid method of measuring students’ musical understanding (Gromko, 1994), and may effectively promote creative music learning (Bamberger, 1986; 1991; Barrett, 2007; Lee 2013; Upitis, 1992; Wiggins, 2009) while opening pathways to more currently relevant and globally diverse forms of musical expression (Strand, 2011; Williams, 2011).

Somewhere, however, there is a disconnect between the fundamental premise of inherent musical creativity and the number of students who are able to express original ideas through music in today’s schools. Consider that less than 6% of K-12 music teachers report including composition tasks on a regular basis in their classes (Strand, 2006), that a majority of music teachers claim to cover improvisation less than any other National Standard for Music Education in the United States (Byo, 1999; Wilson, 2003), that some music teachers say they would prefer to see the National Standards for composing, improvising, and arranging de-emphasized or deleted entirely (Lehman, 2008), and that a contemporary composer like Libby Larsen would express concern for music education that is not relevant to an evolving 21st century global culture by stating, “in music education, or perhaps in all of American music, we impoverish ourselves rather than seeking to understand the world we live in” (Strand, 2011, p. 61).

Larsen suggests that one of the ways to help the music education profession become more relevant to the needs of modern students is to devise new systems of music notation that allow students’ musical knowledge to grow and develop connections with cultures and styles beyond the “parameters derived from a narrow band of Western classical music” (Strand, 2011, p. 59). To facilitate this, she proposes that among music theorists, composers, or music educators, “it is the responsibility of music educators” to lead the development of new notation systems that are more relevant to the needs of modern students (Strand, 2011, p. 59). Perhaps an alternative approach to teaching aural awareness and music literacy that is more inherently intuitive than traditional notation would encourage children to explore their creative musical potential and discover new musical directions that are personally relevant and meaningful.

The purpose of this article is to share my pedagogical approach, objectives, assessments, and reflections as a visiting instructor teaching a 3-week composition project during five lessons plus a day for exit interviews with a 5th grade general music class at a private elementary school in the midwestern United States. Each student’s final composition was created using a new method for developing music literacy based on a simple form of graphic notation that can simultaneously combine simple creative tasks, note writing, and singing activities in real time at the tempo of a live musical performance. Known as Iconic Graphic Notation (IGN) (see Figure 1), this rudimentary method for intuitively representing musical sounds could possibly serve as a system to develop crucial prerequisite components of music literacy and creative musicianship. The development of these components is made possible in the way that IGN may guide students’ aural awareness while reinforcing comprehension of their musical knowledge by fusing the multi-modal cognitive domains of creating, singing, and writing music into a unified experience.

Prerequisite components of creativity have been described as experiences such as listening and performing activities that build an understanding within the parameters which children are asked to creatively work (Wiggins, 2009). Creative musicianship relies on a complex set of higher-level thinking skills utilizing one’s acquired musical knowledge (Krathwohl, 2002; Webster, 2002; 2013). In addition to the application of listening and performing experiences, creative actions are also based on an aural awareness of how the musical imagery in one’s mind can become an intended action that represents one’s imagined idea in an audible musical context.

Brain imaging studies with musical imagery (i.e., thinking about music without audible sounds) have revealed that imagining a musical experience and engaging in a live version of that imagined musical experience produces similar neural activity in the auditory cortex while listening to live melodies (Halpern & Zatorre, 1999; Yoo, Lee, & Choi, 2001), listening to isolated pitch timbres (Halpern et al., 2004), performing complete melodies, (Meister et al., 2004), or performing tonal patterns (Penhune et al., 1998; Zattorre et al., 1996). Additional research on the role of cognitive function in musical imagery by Highben and Palmer (2004) found that people who test high for aural skills are the least disrupted while learning a new piece of music if forced to rely only on their musical imagery, suggesting that the ability to accurately imagine musical sounds facilitates the music learning process. In the case of the composition project reported in this article, the real time immediate feedback and intuitive nature of writing simple musical icons may serve to guide the early stages of aural awareness in students’ brains as they seek to understand how the pitches and rhythms they imagine can be instantly realized by their singing voices.

Before describing the details of the IGN composition project, the ensuing section presents three central principles for why an alternative approach to teaching music literacy and creative musicianship may have merit. These principles are based on the inherent creative potential for music in all people, a natural sequence of learning that builds upon active experience, and the value of balancing structure and creativity in the learning process.

The Rationale For An Iconic Graphic Notation Method

A philosophical challenge rooted in the fundamental premise of this article and tied to calls in our profession to provide creative experiences to all students (Jones, 1986; Strand, 2011; Williams, 2011) is that all music educators should help students not only achieve their inherent musical potential to perform music, but also help students express their original ideas as competently through music as they are able to express themselves through language. To this end, the IGN method was developed based on three central principles of music learning found throughout music education pedagogy and philosophy.

The Inherent Creative Potential For Music In All People

This article promotes a wider definition of musical creativity encompassing any of the ways in which a person produces an original musical idea or represents existing musical knowledge in a new way. Novelty, appropriateness, aesthetic value, and usefulness are all valid goals. However, some writers have suggested that dismissing creative efforts that do not appear to demonstrate historical significance or cultural relevance is not in the best interest of guiding young creative minds (Bamberger, 1996; Barrett, 1996; Flohr & Persellin, 2011; Freire, 1970; Gromko, 1996). Freire argues that narrow definitions of creativity in a hierarchical learning environment inhibit creative thinking, a perspective that has also been identified by multiple music educators (Allsup, 2003; Wiggins, 1999/2000; Claire, 1993/1994). As Barrett has carefully reflected, “… the function of composition and creative experience in the lives of children differs from that of adults in crucial ways” (1996, p. 5). Gromko adds that a “…composition’s worth cannot be judged according to objective standards imposed upon it by a critic who stands at a distance,” and that the role of a teacher “… is to unfold the composition’s layers of meaning in consultation with the child” (1996, p. 75-76). Especially when it comes to guiding the initial steps of musical creativity in children, a supportive pedagogical approach that offers examples and suggestions from knowledgeable others to encourage a child-centered learning environment of self-determined discovery may help to promote inventiveness and spontaneity (Flohr and Trevarthen, 2008). Such an environment may also help to avoid the documented anxieties that can stifle creative effort in traditional performance settings (Wehr-Flowers, 2006; Rosen, 2000).

It is also important to address the perspective that not all musical activities are necessarily creative (Shively, 2002). Performing a work of music that someone else wrote can demonstrate a technically skilled and emotionally expressive form of knowledge representation, but as a creative process such a reproductive performance could be incomplete compared to composing, improvising, or arranging. There may be a neuroscientific basis to support a definition of creative musicianship that differentiates between technically skilled performance on one hand and creative performance on the other. For example, fMRI studies by Limb and Braun involving professional pianists during three different performance tasks (memorized scales, playing a jazz tune from written notation, and playing improvisations on a jazz tune while ‘trading fours’ with another improviser) revealed that the process of improvised music performance consistently produced brain activation patterns that were entirely different from the brain activation patterns implicated by memorized or note reading performances (2008).

Furthermore, in the process of learning to be creative, the quality of a creative act does not necessarily equate to the complexity and technical proficiency of a creative act. Similar to the balance of conditions leading to an optimal experience in flow theory (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990), the educational value of a creative learning activity is dependent upon matching the knowledge and experience level of the learner with the level of complexity and required knowledge necessary to successfully engage in the creative learning task. Reimer has supported the idea that creativity should be taught from the very beginning of a child’s music education right along side the development of performance technique (2003), an idea that also aligns with the declaration by Bruner that if the structure of a learning experience meets the readiness of a learner then “the foundations of any subject may be taught to anybody at any age in some form” (p. 12, 1960).

Experience Precedes Theory As Learning Moves From Simple To Complex

A popular idea in education is that learning from experience offers an initially more effective approach to understanding a new concept than abstract theoretical descriptions like books or lectures to introduce a new concept (Dewey, 1938; Kolb, 1984; Piaget, 1954; Rogers, 1969). Also known as experiential learning, a key provision of this learning theory is the process of actively reflecting on a past experience in order to improve how one might conceptualize a more effective, refined, and advanced approach to that experience in the future (Kolb, 1984). Experiential learning is rooted in Pestalozzian educational philosophy (Holz & Jacobi, 1966) and manifests itself throughout music education with pedagogies that embrace catch phrases like, “Sound before Symbol”, “Rote to Note”, “Simple to Complex”, “Known to Unknown”, and “Macro to Micro”.

Some teachers, however, endorse a contrasting viewpoint which favors teaching music notation as early as possible – an approach that has been suggested to signify fears that students who are initially taught by ear will not reach the same level of music literacy as those who are exposed to notation as early as possible (McPherson & Gabrielson, 2002). Yet, when researchers investigate the conditions that most effectively prepare children for music literacy, they have found that students who are taught music notation without first developing aural awareness for the patterns, motives, and phrases of musical expression are the same students who exhibit the most frustration and confusion trying to read and perform with standard notation (Bamberger, 1996; McPherson & Renwick, 2000).

To prepare students to become literate musicians who are also able to maintain a holistic awareness of musical expression, it appears they must first gain perceptual and cognitive experiences performing musical patterns so that they are able to organize their aural awareness and understand the characteristics of music that are most meaningful to them. These meaningful characteristics are rarely individual notes, but rather, they represent interconnected elements of music that provide a holistic experience built out of the nuances of a phrase, the climax of a melody, and the eventual release from a tense musical passage. According to Bamberger, preparing students to recognize and express these meaningful characteristics as literate musicians requires that they initially experience what it feels like to hear, perform, and create them: “The kinds of elements and relations novices attend to in making sense of music as it unfolds in real time, are highly aggregated, structurally meaningful entities such as motives, figures, and phrases” (1996, p. 42).

Offering the types of experiences that allow children to understand how the patterns of music interconnect is a fundamental goal of the IGN method. Bruner’s modes of representation provide a theoretical basis for the development of this method with his proposal that learning begins with an experience that sequentially evolves across three stages of development: (a) an enactive mode in which actions and experiences shape the initial learning process; (b) an iconic mode in which knowledge of enactive learning experiences is organized and strengthened by using intuitive images that represent the elements of knowledge that they look like; and (c) a symbolic mode in which abstract symbols like letters, numbers or notes are used to represent the organization of knowledge with rules or laws to guide theoretical understanding (1966, p. 44). A simple example of an icon is the picture of a folder on a computer desktop screen. This little image is obviously not a real folder, but it reveals that its function is to organize information on our computer by reminding us of the real folders we have enactively experienced in the past.

Iconic learning tools are nothing new for music learning either, such as the Curwen hand signs that are so prominently employed in the Kodaly method featuring subtle iconic representations for the notes in a diatonic scale (though these hand signs seem to occur throughout all areas and ages of music education, especially at the elementary level). For example, a solid and firm fist represents the tonal center tonic note, a thumbs down sign represents the 4th scale degree (Fa) and our perceived tendency to resolve it down a half step to the third scale degree, whereas an upward pointing index finger represents the 7th scale degree (Ti) and suggests our perceived tendency to resolve up a half step to the tonic note. Additionally, music teachers and students often raise and lower their hands up and down the solfege scale to suggest the pitch height of the hand sign they are using.

Many musicians are probably aware of this iconography where the meaning of a thing is intuitively suggested by the way a thing appears. Yet, to a young child learning to perform and understand how notes can be organized within a key signature, Curwen hand signs provide a helpful iconic/kinesthetic tool that builds upon the memory of enactive singing experiences to develop an understanding for how the symbolic notes in a diatonic scale are represented with standard notation. The IGN method (see Video 1) was developed to specifically serve the needs of an intermediary iconic stage for students with enactive singing and performing experience, but who may not yet understand how to turn the notes they imagine in their mind into an easily realizable musical pattern to be performed, read, and written using standard notation.

By offering immediately recognizable icons, the IGN method may be used to reinforce the initial stages of aural awareness and music literacy in a student’s mind by offering a way to economize the musical knowledge acquired during previous listening and performing experiences. Easily imitable, readable, performable, or producible icons can be used during progressively challenging developmental real time tasks with student written IGN worksheets to record the notes they perceive they are singing, taking down for aural dictation, or creating from available tonal patterns. This sequence of learning built around iconic imagery resonates with the imitate-explore-create approach with elemental music endorsed by Orff-Schulwerk (1963) as well as other experiential learning simple to complex approaches to creative musicianship (Azzara and Grunow, 2006; Gordon, 2003; Christian Howes, 2014; Kratus, 1995). All of these approaches favor the development of aural awareness, performance ability, and creative musicianship through a sequential development from simplistic convergent outcomes toward progressively complex and abstract divergent outcomes. In other words, the process of learning moves sequentially at a pace that is shared by the teacher and the students in the development of the prerequisite components necessary for more advanced ways of representing their musical knowledge.

The Value of Balancing Structure and Creativity In The Learning Process

Creative thinking may mark the highest order of cognition (Krathwohl, 2002), yet the value of creatively expressing what one has learned is an important way of representing knowledge with each step of a child’s learning process (Remier, 2003; Bruner, 1960). In some cases, particularly for children with autism spectrum disorders, a consistently structured and predictable learning environment may be more appropriate to their needs (Iovannone, R. et al., 2003), but in many teaching situations, writers suggest that creative thinking skills flourish in a balance of convergent and divergent outcomes (Cropley, 2006; Guilford, 1957; Webster, 2002).

An example of this principle of balance is to imagine a spectrum of potential learning outcomes for any learning activity: On one far side of this spectrum is a convergent and specific learning target for the given task (i.e., just one right answer) and on the other far side of the spectrum is a limitless spread of divergent outcomes (i.e., an infinity of right answers). Neither absolute edge of this imagined spectrum offers an ideal format for teaching students to become creative thinkers. If a student is directed to find the one “right” answer in a task that claims to develop innovative thinking skills then what exactly is the creative thought process that the student has learned to develop? On the other hand, facing an infinite spread of creative options without guidance or parameters can be just as daunting. Even composers like Stravinsky knew the intimidating challenge of starting out on a creative task sufficient structure:

As for myself, I experience a sort of terror when, at the moment of setting to work and finding myself before the infinitude of possibilities that present themselves, I have the feeling that everything is permissible to me. If everything is permissible to me, the best and the worst; if nothing offers me any resistance, then any effort is inconceivable, and I cannot use anything as a basis, and consequently every undertaking becomes futile (1970, p. 63).

To his relief, what Stravinsky discovered is that the process guiding him from the terror of too many options is similar to the structure teachers can provide to their students:

I shall overcome my terror and shall be reassured by the thought that I have the seven notes of the scale and its chromatic intervals at my disposal, that strong and weak accents are within my reach, and that in all of these I possess solid and concrete elements which offer me a field of experience just as vast as the upsetting and dizzy infinitude that had just frightened me. Let me have something finite, definite – matter that can lend itself to my operation only insofar as it is commensurate with my possibilities (1970, p. 64).

Helping students discover the best balance of structure and creativity by adjusting the scaffolding of the learning environment to their immediate needs allows students to more successfully approach creative tasks with well-defined, specific parameters in which they are able to tackle the musical challenges that are most suited to their ability level. Scaffolding refers to the social parameters of the learning environment based on the interactions between learners and knowledgeable others (Palincsar & Brown, 1984). Examples of scaffolding that evolve progressively to meet students’ needs include quality demonstrations of musical performance, providing comments of formative feedback, or any of the interactions that shape a learning process. As Webster has said, “…creative thinking is a dynamic process of alternation between convergent and divergent thinking, moving in stages over time” (2002, p. 26). The objective for teachers seeking to guide their students toward creative musicianship is to serve a balanced diet of instruction that is neither too technically cold with the tedium of excessive repetition nor too creatively hot with the intimidating challenge of infinite outcomes.

Summary Of The IGN Method

When one considers the research endorsing teaching music by using alternative notation systems, proposals to provide opportunities for all students of all ages to learn creative musicianship, combined with the value of a sequentially balanced experiential learning processes that builds upon experience toward more advanced forms of understanding, it may be possible to blend a common theme from all of these ideas. Just as some music teachers have sought to pull ideas from multiple schools of thought into one music teaching approach (Nash, 1974), the IGN method was designed to simplify how all of these ideas could be applied into a new approach for teaching aural awareness, music literacy, and creative musicianship in the early stages of musical development. (see Figure 1 and Video 1).

Video 1. A live demonstration of real time music writing with Iconic Graphic Notation rhythm patterns.

Three primary goals for the IGN method are:

- To strengthen students’ aural awareness for the music they imagine in their minds.

- To engage students in developmentally appropriate creative music activities based on their ability to represent personal musical imagery.

- To provide experiences that may serve to strengthen students’ comprehension of music literacy.

Description of a 3-Week Composition Project Using Real-Time IGN

During a span of 3 weeks, a class of thirteen 5th grade students worked with me as a visiting instructor for a total of five, 30-minute lessons twice a week, plus a sixth day to conduct one-on-one exit interviews and gather the students’ personal reflections on the composition project. The first four lessons involved student performing and creative activities while the fifth lesson served as a concluding day to read, listen, and discuss the main musical characteristics in each students’ IGN melody transcribed into standard notation and performed for the class by guest musicians. Each of the five lessons sought to follow a sequential approach to develop students’ familiarity with creating musical patterns:

- Lesson One: Rhythmic Awareness Training and Review of Basic Rhythm Patterns

- Lesson Two: Rhythmic Foundations With Iconic Graphic Notation

- Lesson Three: Tonal Awareness Training and Review of Elemental Tonal Patterns

- Lesson Four: Composing Music With 2-Note Melodies

- Lesson Five: Concluding Performances With Student Identification and Discussion for the Main Musical Characteristics of IGN Melodies in Standard Notation

- Student Exit Interviews

During planning stages with the regular general music teacher, he stated that the students’ previous music learning experiences were focused on singing and movement with an emphasis on developing music literacy through reading, clapping and saying note patterns in standard notation. None of the students were familiar with solfege syllables nor had any of them received private training in music, although two students reported that composing music was something they had done informally with their parents at home.

To avoid the composer’s terror of infinite possibilities that Stravinsky alluded to, the structure of the IGN method allows an instructor to adjust the number of factors that may prove overwhelming for a novice student who is uncertain about how to make creative musical decisions. Specifically, several constant musical and pedagogical factors were employed throughout the composition project providing a structured format to help students focus their creative attention on generating basic rhythm patterns from only two pitch options (sol and mi) in 4/4 meter while avoiding potential distractions due to other musical elements (e.g., dynamics, tempo variation, or choosing from more pitch options than their aural memory might allow). The following factors provided a structural context throughout the learning process as the instructor initiated and guided the group performance and creative music tasks during the project:

- All musical activities used a consistent steady tempo (m.m. = 70 BPM)

- Every performance or creative task was initiated with a different 4-beat call off by the instructor (e.g., “One, Two, Draw and Say” to the rhythm of “1 2 3 + 4”). Each 4-beat call off varied with different words, pitches, and rhythm combinations to avoid influencing students’ creative choices.

- All musical tasks engaged students in multiple cognitive domains of knowledge, such as verbally and kinesthetically chanting the rhythm pattern that students were clapping, or singing the pitch pattern that they were simultaneously writing.

A brief summary for each of the lessons is provided below followed by a list of the day’s objectives. Sample demonstrations of the IGN methods used in real time by the students is offered in Videos 2, 3, 4, and 5. Figures 2 and 3 present examples of completed student IGN worksheets.

Lesson One: Rhythmic Awareness Training and Review of Basic Rhythm Patterns

The main goal of the first lesson in the composition project was to review and strengthen the aural skills necessary for students to accurately imagine the rhythm patterns in their mind that they would eventually be singing and writing on paper later on in the project. Kodaly rhythmic notation was used exclusively for today’s lesson since this was the system students had been trained in thus far. Creative musical tasks are introduced to the students individually in step 4 and with partners in step 5.

Lesson One Learning Objectives

- Students will clap and say 4-beat rhythmic echo exercises from the instructor using the Ta Ti-Ti counting system with a variety of note combinations (half notes to 16th notes).

- Error-detection: Students will accurately identify the one rhythm pattern that did not have 4-beats from multiple groups of rhythm pattern options on the board.

- Students will write aural dictation in standard notation for instructor provided rhythms.

- Students will individually write self-created 4-beat rhythm patterns on paper. They will clap, chant, and independently performed their rhythm for the class.

- Student partner pairs will combine their 4-beat rhythm patterns to form an 8-beat pattern. Partners will practice together, then chant and perform their combined 8-beat rhythm pattern with body percussion for the entire class.

Lesson Two: Rhythmic Foundations With Iconic Graphic Notation

After an instructor demonstration of the similarities between Kodaly rhythmic notation, standard notation, and IGN to begin the second lesson, students transferred the rhythmic composition skills they had demonstrated in the previous lesson to the IGN method.

Lesson Two Learning Objectives

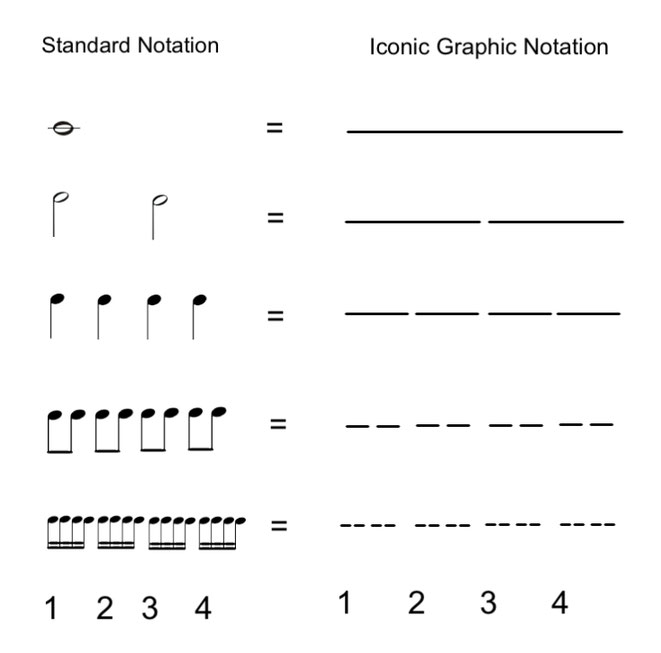

- Instructor will demonstrate how standard notation rhythm patterns such as “Ta Ti-Ti Ta Ti-Ti” can be written as “– – – – – -”, followed by a brief explanation and demonstration of the rhythmic equivalency between standard notation and IGN (Figure 1).

- Students will engage in guided practice writing IGN whole note lines while counting a 4-beat pulse out loud with a steady tempo across their worksheet page (see the four unbroken lines representing the whole note drawing practice session in Figure 2).

- Students will write aural dictation using IGN for instructor provided rhythms.

- Students will individually write self-created 4-beat rhythm patterns on paper using IGN. They will successfully clap, chant, and independently perform their rhythm for the class.

- Student partner pairs will combine their 4-beat IGN rhythm patterns to form an 8-beat pattern. Partners will practice together, then chant and perform their combined 8-beat rhythm pattern with body percussion for the entire class.

NOTE: at the time this worksheet was completed the IGN method was referred to as “Scribing”.

Video 2. Instructor provides an IGN demonstration of rhythm pattern composition options followed by students engaging in simultaneous real time rhythmic creative writing and chanting tasks using IGN (Lesson 2, step 4).

[NOTE: Permission has been given by the host school principal for all minors present in these videos to share their image with the public. Also present in these videos are music education majors from the author’s institution who were assisting in this lesson.]

Lesson Three: Tonal Awareness Training and Review of Basic Tonal Patterns

Pitch differences in the IGN system are represented by the vertical height of the note lines drawn on the page using a staff system similar to a percussion stave. For example, with the 2-note worksheet that the 5th graders used, they drew their “high” note lines above a central staff line and they drew their “low” note lines below the staff line (see Figure 3). Given that the 5th graders in the IGN composition project had not received any prior solfege training, combined with the limited available time to complete the composition project, a remedial phase was provided to review and strengthen only two tonal patterns for students to use in their compositions. Specifically, instead of starting with an entire major or pentatonic scale of solfege syllables, the initial foundation of their tonal awareness was based on either the Sol or Mi pitches in combination with any of the rhythm patterns they had developed during Lessons One and Two. To ease the students into the relatively new musical imagery expectations they needed to meet for this project, I also chose the most familiar words for them to sing by representing Sol or Mi with “high” or “low” respectively with each of the sequential lesson steps.

Lesson Three Learning Objectives

- Students will sing and show Curwen hand signs in echo exercises with the instructor using tonal patterns for a variety of rhythms from half notes to 16th

- Error-detection exercises: students identified the one 4-beat pitch pattern that did not match the instructor-provided pitch pattern from groups of multiple choice pitch pattern options on the board.

- Students will write aural dictation of 4-beat pitch patterns provided by the instructor using the IGN system.

[NOTE: Some students chose to title their compositions (e.g., “Marshmellows”).]

Lesson Four: Composing Music With 2-Note Melodies

Students were familiar with the IGN method and able to sing and write their original musical ideas within the structured format parameters using “high” or “low” pitches (i.e., Sol or Mi) combined with any of the rhythmic patterns they had become familiar with in the previous phases of the composition project. By the end of this lesson, all of the students were able to compose an original melody using two pitches and a variety of rhythm pattern combinations for four bars of music in common time.

To encourage reflection on their learning experiences and to help refine their creative choices, students were invited to check their work after generating each pattern to make sure they had accurately written down what they imagined and intended in their singing. During steps 2-4, the instructor would call for repetition or for students to self-assess the difficulty of the pattern they most recently created. When a high rate of confusion was observed, the instructor would ask the students to self-assess their work and create a simpler melody in the ensuing creative task. On the other hand, when students appeared highly successful and a low rate of confusion was observed, the instructor would ask the students to self-assess and create a more complicated melody in the ensuing creative task (for an example of this student self-assessment approach, see the last 30 seconds of Video 2).

Lesson Four Learning Objectives

- Review: Students will write aural dictation using IGN for 4-beat rhythm patterns provided by the instructor.

- Review: Students will write aural dictation using IGN for 4-beat pitch and rhythm patterns with Sol or Mi provided by the instructor.

- Students will individually sing and write self-created 4-beat pitch and rhythm patterns using IGN.

- Students will individually write self-created 8-beat pitch and rhythm patterns on paper using IGN.

- Students will individually write self-created 16-beat pitch and rhythm patterns on paper using IGN.

Video 3. Students practice generating original 4-beat tonal patterns; a student volunteers to share a self-composed tonal pattern with the class; all students demonstrate a transition moment as they shift from representing musical knowledge in the enactive mode to representing musical knowledge in the iconic mode.

Video 4. Students demonstrate the simultaneous creation of singing and writing music with IGN in real-time.

Video 5. Students demonstrate the simultaneous performance of their individual 16-beat compositions with IGN in real-time.

Lesson Five: Concluding Performances in Standard Notation With Reflective Discussion About the Main Musical Characteristics of Students’ Melodies

As a concluding activity on the final day of the unit, music education majors from the author’s institution transcribed the students’ IGN melodies into standard notation and performed them for the class as a unison melody on trumpet and trombone with basic harmonic accompaniment on piano. The transcribed melodies were displayed on the classroom digital board so that all of the students could read and listen to a live instrumental performance of their composition in standard notation.

The last few minutes of Lesson Five involved a closure activity to engage students in a discussion of which two students’ melodies might sound interesting when combined together. A sample combination of two students’ melodies with contrasting elements was performed, followed by a prompt from the instructor to focus the students’ attention toward which melodies appeared to have opposite characteristics (e.g., short notes vs. long notes, or high notes vs. low notes). The class ended with students volunteering personal reasons to explain why the characteristics of particular melodies would sound well together followed by the guest musicians obliging the students’ comments and offering impromptu performances of student-suggested melody combinations.

Lesson Five Learning Objectives

- Students will read and listen to an arranged performance of their IGN melody.

- Students will read and listen to an arranged performance of their classmates’ IGN melodies.

- Students will identify a main musical characteristic from their IGN melody (e.g., high notes, low notes, long notes, short notes, melodic sequence, other).

Reflections On The Pedagogy Of Creating, Writing, And Singing In Real Time

Within the first few minutes of being exposed to the IGN method, students were able to simultaneously chant or sing, create, and write original music patterns in real time at the tempo of a live musical performance. IGN allows students an inexpensive initially simple, yet gradually complex method to write their musical ideas as they are thinking and performing them – an approach that has not really been a large part of traditional music pedagogy. Writing a quick and simple real time visual record of the note patterns a student is imagining and singing offers a useful learning tool to help focus aural awareness while providing a musically creative opportunity.

The value of organizing our linguistic thoughts by speaking and writing words almost as quickly as we can think the words we wish to express is something that every literate person has been able to realize. There may be an untapped opportunity in music education to help students who are seeking to organize their musical thoughts by offering them the means to write the notes they are creating in their mind just as quickly as they can sing them. IGN is not intended to replace standard notation. In fact, IGN is intended to strengthen a student’s eventual transition to reading and writing with standard notation. However, anyone who has ever seen how long it takes some children to draw a quarter note may recognize that an alternative and simplified system of notation may offer a wider gateway to the world of music literacy and creative musicianship by enabling children to more easily connect their listening and performing experiences to their writing and creating experiences.

The IGN lessons in the composition project revealed three potential benefits specifically related to a real time music creating/singing/writing process:

- Improved Assessment Capabilities: Real time music writing offers music teachers enhanced opportunities for using formative assessment. An instructor can more readily identify students having difficulty with beat awareness if they are observed not drawing a line with a steady speed across the page, or if they are not stretching their whole note IGN line all the way through to the end of count four on their worksheet.

- Increased Student Focus: Real time music writing offers students a written record of their music learning process that appears to strengthen their working memory and allows them to focus on both aural and visual feedback for the musical task they are doing.

- Simultaneous Performance of Multiple Learning Styles and Ability Levels: Real time music writing may improve the concentration of students while performing improvisation and composition activities simultaneously by helping them focus on the personal note patterns they are creating and performing while others around them are performing different patterns of varying complexity at the same time (see Video 4 and Video 5).

Furthermore, a more subtle benefit that arose during the composition project was how the real time IGN method promoted a constructivist learning atmosphere. Constructivist teachers serve as facilitators in student-centered learning environments by placing the responsibility for learning in the hands of the student, (Shively, 2002). While it is evident in the videos that the instructor was still a focal point during the class activities, there were successively greater elements of constructivism as the IGN lessons progressed by leading students into decision-making activities that allowed them to take responsibility for the tonal patterns they were most capable of producing. Students took an active role in reflecting, self-assessing, and discovering how to solve the musical challenges for their unique creative tasks as the instructor took on a greater role as a facilitator in student learning. If there were any students displaying confusion or an inability to produce their created note patterns with the class then everyone was asked to consider what they just tried to do and create an easier pattern next. If the entire class appeared to be successfully creating/writing/singing tonal patterns with a steady beat then everyone was asked to consider what they just tried to do and create a more complicated pattern next. This reflects some of Younker’s insights regarding the nature of effective teacher feedback in a creative learning environment: “…questions should focus students’ thinking on how they might proceed, what they want to do with the materials, and how they want their compositions to sound” (1996, p. 237).

Eventually the students were able to engage in multiple sequences of this create/self-evaluate/create sequence very smoothly in rapid succession (see an example of this self-assessment process during the last 30 seconds of Video 2). The students were self-evaluating the appropriate level of challenge for their unique point in the learning process by deciding whether to make their next tonal pattern more challenging (i.e., lots of pitch changes and rhythmic activity) or more comfortable (i.e., static rhythms and pitch changes). These moments of self-discovery are powerful learning experiences – a process Stravinsky described as finding the musical challenge that is “commensurate with my possibilities” (1970, p. 64).

Assessment and Student Feedback From The IGN Composition Project

All of the students were able to independently demonstrate all of the objectives listed in the sequential steps for each of the four lessons outlined in the composition project by the end of each lesson day. All of the students were able to verbally identify a main musical characteristic from the standard notation transcription of their melody in Lesson Five. Several of the students excitedly participated in the closing discussion in Lesson Five about who’s melody would work well when paired with another student’s melody, however, the class time expired before all of the students were able to participate in this discussion and offer suggestions for “mash ups” (a term the students quickly adopted to describe this process).

Each of the lesson objectives were guided by carefully observing the students’ progress and offering specific instructor feedback, providing student self-assessment opportunities, providing frequent musical performance models, and allowing for repetitive student practice as necessary before moving on to the next objective in the lesson. The assessment of students’ comprehension for the lesson objectives was conducted by observing individual and group performances as well as reviewing individual written work after each lesson that was recorded in a checklist of project learning objectives. All of the students produced successfully completed hand-written IGN worksheets for each day of the composition project.

An indicator of the heightened focus that the students were able to achieve using the IGN method is demonstrated by the way they were able to sing their independent melodies as a class all at the same time by producing a rhythmic jumble of minor third harmonies (see Videos 4 and 5). My observations of the class indicated that all students participated in the chanting and singing for each of the IGN project learning activities at all times. One unknown that lingers, however, is that it is difficult to assess from the video footage and from live observations if all of the students were able to sing their own melody simultaneously or if only some of them were singing their own music while others became distracted and mimicked the voices around them. Evidently, enough students were singing their own music to create a texture of harmony with the class, but how many were independently focused on their original musical ideas remains uncertain.

Reflections From Students

In one-on-one interviews after the project was completed, all of the students responded to five consistent questions, plus an open-ended invitation to share any other thoughts they had about the project. The students unanimously agreed that they felt like they “learned about how to compose” by completing this project. All of the students reported that this experience was either one of their favorite, or in the case of one student, their top favorite musical experience of all time. Students also reported that participating in the composition project was interesting and enjoyable, and that the IGN system was helpful in their approach to creating music. When asked if the IGN method was boring or too easy, none of the students agreed with this suggestion. When asked to share their personal thoughts about the project, the most common statement was that they really liked getting to make up their own music. A few students offered additional insights:

Samantha (none of the student’s actual names are used) summarized the difference between Lesson One and Lesson Two when she remarked, “Writing lines was the easiest way instead of drawing the notes out.” Max shared that the IGN project changed the way he thinks about other musical experiences now: “I’ve never even thought about the notes like that before in High-Low. Usually I just sing the music – I didn’t think about the notes.” Finally, two of the thirteen students volunteered comments that may reflect a shift in their personal musical identities: Chase said, “I’ve been interested in music all my life but this helped me feel like I could do more music than I’ve done before.” Tammie, described by her music teacher as one of the best singers in class, said, “I never really thought of myself as a music person before and this made me think I can do music.”

Implications For Music Education

In summary, there are several potential implications the IGN method may offer practicing music educators, particularly in the teaching of music literacy and creative musicianship. The IGN method offers:

- Real time aural and visual feedback supporting aural development and music literacy for pitch relationships and rhythm patterns.

- A simple pedagogical approach providing creative musicianship learning opportunities to all children.

- A real time multi-modal activity simultaneously engaging kinesthetic performance, music writing, and creative musicianship activities at the tempo of a live performance.

- An iconic learning system that may strengthen the cognitive connection between students’ enactive music experiences and their understanding of symbolic music knowledge such as standard notation.

- A pedagogical approach to help students find a balance of structure and creativity that is personally suited to their individual learning needs.

- An instructional aid providing teachers with easily produced, inexpensive, and efficient individual student assessment records for music learning activities.

- An evolving constructivist atmosphere enabling student determined learning and creative tasks with students of different music ability levels at the same time.

Future Directions

Given the newness that composition lessons held for the 5th graders in this project, the parameters of the lessons were set on the more convergent side of the structure-creativity spectrum. A major test for the potential viability of IGN tasks in the future will be to determine if students are able to advance its use toward less structured and more open-ended creative activities that eventually expand to include less atomistic traits and more authentic note options, such as with pentatonic or diatonic scales.

Thus, another of the most immediate questions to address in future applications of the IGN method is to investigate if the learning objectives achieved during a 3-week composition project with a relatively small class size in a private school can be reproduced and advanced with extended durations of instructional time with larger class sizes at both public and private institutions. An additional future goal is to increase the role of a student-centered learning environment. As students become more experienced and familiar with the IGN method they would conceivably be more enabled to create musical patterns on their own without the need for an instructor to call off every creative task. Long term learning experiences with the IGN method would also represent a shifting balance from the convergent side of the structure/creativity spectrum toward more divergent learning outcomes with a broad range of creative options allowing students to advance into a more holistic and authentic musical context. This more experienced student context would definitely feature more note options, and would sequentially expand to involve a variety of other creative scenarios including varying tempos and textures, arrangements of familiar melodies, explorations of harmony by layering IGN melodies from similar chord progressions, and having students work in pairs to combine their IGN melodies and encouraging them to perform with each other. Further investigation with this method seems warranted.

Final Thoughts

A valid concern might be to suspect that the students in the composition project were randomly generating IGN patterns without engaging any musical imagery during the creative music tasks. If students were only engaged in writing IGN patterns then this concern would have more merit. What possibly makes this concern less viable is the way that students engaged in a multi-modal activation of cognitive domains that combined at a minimum the use of musical, visual, and kinesthetic knowledge, as well as the mental capacity to executively coordinate these ways of knowing. The pitch options in this project were simple, but the cognitive complexity required to participate suggests that there may be too many domains of knowledge in play for a student to successfully fake doing all of them at the same time while still keeping a steady pulse.

Another concern that might arise is that the melodies the students produced for this project were simple, seemingly random, and not an authentic representation of culturally relevant music nor a typical example of aesthetic creative work. However, the goal of this project was not to teach students how to compose sophisticated or exceptional melodies. The main goal was to help students successfully perform and write the tonal patterns of music that they initially imagined in their minds. For children, the first books they learn to read with lines like “Goodnight room. Goodnight moon” (Brown, 1975) are the world of literature to their young minds. These first steps of reading may stimulate a lifetime of language arts. To young musical minds, the IGN method may offer a similar form of elegant redundancy that can build toward a wider world of musical creativity and literacy as students mature into advanced stages of musical understanding.

To reflect on the primary goal of this project, the experience I was most hopeful for students to realize was the feeling of imagining a musical pattern in their mind followed immediately by the sensation of hearing their voice sing the exact pattern they had imagined while seeing their hands confirm a written representation of that pattern on a page. Understanding that they are able to control and express their musical thoughts may represent the building blocks leading to higher-order cognitive thinking in music. Of course, it is nearly impossible to know what students imagined in their minds as they sang and wrote their musical patterns, but based on the students’ successful completion of the project’s lesson objectives, the rapt attention students demonstrated in class combined with the strong positive sentiments that all of the students shared about making their own music, there is reason to suspect that the students believed something important was happening as they produced their musical patterns.

Finding the appropriate balance of structure and creativity for students is a delicate process as teachers provide what’s necessary without weighing them down with what’s burdensome. In the words of Wiggins, “Students need opportunities to make music on their own – without unnecessary teacher controls. If we offer students such opportunities, we will see them soar in ways none may have thought possible” (1999, p. 35). While the IGN method may appear to have presented a high degree of teacher control, my position is that its limitations on divergent creative options were necessary and appropriate to the level of students’ musical understanding and that gradually, the balance of control was shifting from instructor to student.

The results of this project support the conclusion that expressing an original idea through music produces a deeply personal way of representing one’s musical knowledge and possibly even shaping one’s identity. This kind of meaningful connection appears to be possible even within a highly structured context with limited divergent options if the knowledge and experience level of the learner is balanced by the level of structural quality and complexity in the learning activity. The more inexperienced a student’s musical knowledge, the greater the balance of quality demonstrations and limited divergent outcomes needs to be in order to meet children at their level of understanding. This type of balance may not suit the needs for all creative learning experiences, but in some cases, particularly with beginners, the IGN method is well suited to help novice musicians approach creative musicianship and music literacy at an appropriate challenge point.

Finally, the students’ closing comments during their exit interviews seemed to highlight a consistent theme – that a creative demonstration of musical knowledge is possibly the most meaningful and intrinsically motivating part of a music learning process. Throughout the project, there were no salient rewards offered for using the IGN method other than the opportunity to create. When children are given the means to express an original musical idea at their level of understanding it builds confidence and generates interest in their musical potential. This is something all children are capable of learning.

References

Allsup, R. E. (2003). Mutual learning and democratic action in instrumental music education. Journal of Research in Music Education 51(1), 24-37.

Amabile, T. M. (1996). Creativityin context.Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Azzara, Christopher D., & Grunow, Richard F. (2006). Developing musicianship through improvisation: Vocal edition 1. Chicago: GIA Publications, Inc.

Bamberger, J. (1986). Cognitive issues in the development of musically gifted children. In: R. J. Sternberg and J. E. Davidson (Eds.) New Conceptions of Giftedness. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bamberger, J. (1991). The Mind behind the Musical Ear. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bamberger, J. (1996). Turning music theory on its ear. International Journal of Computers for Mathematical Learning, 1(1), 33-55.

Barrett, M. S. (1996). Freedoms and constraints: Constructing musical worlds through the dialogue of composition. In: Hickey, M. (Ed.), Why and how to teach music composition: A new horizon for music education (31-54). Reston, VA: MENC: The National Association for Music Education

Barrett, M. S. (2004). Thinking about the representation of music: A case-study of invented notation. Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education, 161/162, 19-28.

Barrett M. S. (2007). Invented notations: a view of young children’s musical thinking. Research Studies in Music Education, 8(1), 2–14, doi: 10.1177/1321103X9700800102.

Blacking, John. (1973). How musical is man? Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Brown, Margaret Wise. (1975) Goodnight moon. New York: Harper Collins Publishers.

Bruner, Jerome. (1960). The process of education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bruner, Jerome. (1966). Toward a theory of instruction. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Byo, S. J. “Classroom Teachers’ and Music Specialists’ Perceived Ability to Implement the National Standards for Music Education,” Journal of Research in Music Education 47, no. 2 (1999): 111–23;

Claire, L. (1993/1994). The social psychology of creativity: The importance of peer social processes for students; academic and artistic creative activity in classroom contexts. Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education, no. 119, 21-28.

Cropley, A. (2006). In praise of convergent thinking. Creativity Research Journal, 18(3), 391-404, doi: 10.1207/s15326934crj1803_13

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. New York: Harper & Row.

Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and Education. Toronto: Collier-MacMillan Canada Ltd.

Flohr, J. W. (1985). Young children’s improvisations: Emerging creative thought. The Creative Child and Adult Quarterly, 10(2), 79-85.

Flohr, J. W., & Trevarthen, C. (2008). Music learning in childhood–Early developments of a musical brain and body. In W. Gruhn, & F. Rauscher (Eds.), Neurosciences in music pedagogy (pp. 53-99). Hauppage, New York: Nova Science Publishers.

Flohr, J. W. & Persellin, D. C. (2011). Applying brain research to children’s musical experiences. In: Burton, S. L., and Taggart, C. C. (Eds), Learning from young children: Research in early childhood music (3-22). MENC: The National Association for Music Education.

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Continuum International Publishing Group Inc.

Gardner, H. (1999). Intelligence reframed. New York: Basic Books.

Gordon, Edwin E. (2003). Improvisation in the music classroom: Sequential Learning. Chicago: GIA Publications, Inc.

Gordon, Edwin E. (1997). Learning sequences in music: Skill, content, and patterns – A music learning theory. Chicago: GIA Publications, Inc.

Gromko J. (1994). Children’s invented notations as measures of musical understanding. Psychology of Music, 22(2), 136–147.

Gromko, J. (1996). Children composing: Inviting the artful narrative. In: Hickey, M. (Ed.), Why and how to teach music composition: A new horizon for music education (31-54). Reston, VA: MENC: The National Association for Music Education

Guilford, J. P. (1957). Creative abilities in the arts. Psychological Review, 64(2), 110-118. doi: 10.1037/h0048280

Halpern, A. R., & Zatorre, R. J. (1999). When that tune runs through your head: a PET investigation of auditory imagery for familiar melodies. Cerebral Cortex, 9, 697- 704.

Halpern, A. R., Zatorre, R. J., Bouffard, M., & Johnson, J. A. (2004). Behavioral and correlates of perceived and imagined musical timbre. Neuropsychologia, 42(9), 1281-1292.

Hickey, M. (1996). Creative thinking in the context of music composition. In: Hickey, M. (Ed.), Why and how to teach music composition: A new horizon for music education (31-54). Reston, VA: MENC: The National Association for Music Education

Highben, Z., & Palmer, C. (2004). Effects of auditory and motor mental practice in memorized piano performance. Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education, 159, 58-65.

Hodges, D.A. (2005). Why Study Music? International Journal of Music Education. 23(2), 111- 115.

Holz, Emil A., and Jacobi, Roger E. (1966). Teaching Band Instruments to Beginners. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc.

Howes, Christian. (2013). Jazz violin, string recording, and jazz violin lessons. Retrieved from http://christianhowes.com

Jones, T. (1986). Education for creativity. British Journal of Music Education, 3(1), 63-78.

Koelsch, S., Gunter, T. C., v Cramon, D. Y., Zysset, S., Lohmann, G., & Friederici, A. D. (2002). Bach speaks: A cortical “language-network” serves the processing of music. Neuroimage, 17(2), 956-966.

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning Experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Krathwohl, D. R. (2002). A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy: An overview. Theory Into Practice. 41(4), 212-218.

Kratus, John. (1990). Structuring the Music Curriculum for Creative Writing. Music Educators Journal, 76(9), 33-37.

Kratus, John. (1995). A developmental approach to teaching music improvisation. International Journal of Music Education, 26, 27-38. doi: 10.1177/025576149502600103

Lehman, P. (2008). A vision for the future: Looking at the standards: Should MENC revise the 1994 National Standards to reflect current conditions? A task force studies the question and makes some suggestions. Music Educators Journal, 94(4), 28-32. doi:10.1177/00274321080940040103

Lee, Pyng-Na. (2013). Self-invented notation systems created by young children. Music Education Research, 15(4), 392-405.

Levitin, D., & Menon, V. (2003). Musical structure is processed in “language” areas of the brain: a possible role for Brodmann Area 47 in temporal coherence. Neuroimage, 20(4), 2142- 2152.

Limb, C. J. & Braun, A. R. (2008). Neural substrates of spontaneous musical performance: An fMRI study of jazz improvisation. PLoS ONE 3(2) e1679.

Mayer, R. (1999). Fifty years of creativity research. IN: Sternberg, R. (ed.) Handbook of creativity (449-460). New York: Cambridge University Press

McPherson, G. E. & Renwick, J. (2000). Self-regulation and musical practice. In C. Woods, G. B. Luck, R. Brochard, F. Seddon, And J. A. Sloboda (Eds.), Proceedings of the sixth international conference on music perception and cognition. Keele, UK: Keele University, Department of Psychology.

McPherson, G. E. & Gabrielson, A. (2002). From sound to sign. In: Parncutt, R. and McPherson, G. E. The science and psychology of music performance: Creative strategies for teaching and learning (99-116). New York: Oxford University Press.

Meister, I. G., Krings, T., Foltys, H., Boroojerdi, B., Muller, M., Topper, R., & Thron, A. (2004). Playing piano in the mind: An fMRI study on music imagery and performance in pianists. Cognitive Brain Research, 19(3), 219-228, DOI: 10.1016/j.cogbrainres.2003.12.005

Merriam, Alan. (1964). The anthropology of music. Chicago: Northwestern University Press.

Mithen, S. (2005). The singing Neanderthals. The origins of music, language, mind and body. London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson.

Moog, H. (1976). The development of musical experience in children of preschool age. Psychology of Music, 4(2), 38-45.

Moorhead, G. E. & Pond, D. (1941). Music of young children. Santa Barbara, CA: Pillsbury Foundation for the Advancement of Young Children.

Nash, Grace. (1974). Creative approaches to child development with music, language, and movement: Incorporating the philosophies and techniques of Orff, Kodaly, and Laban. Welsh, R. (Ed.). Alfred Publishing, LTD.

Nettl, B. (2000). An ethnomusicologist contemplates universals in musical sound and musical culture. In: Wallin, N.L., Merker, B., and Brown, S. (Eds.), The Origins of Music (pp. 463–472). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Orff, Carl. (1963). The Schulwerk: Its origin and aims. Music Educators Journal, 49(5), 69-74.

Penhune, V. B., Zatorre, R. J., & Evans, A. (1998). Cerebellar contributions to motor timing: A PET study of auditory and visual rhythm reproduction. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 10, 752-765.

Palincsar, A. M. & Brown, A. L. (1984). Reciprocal teaching of comprehension-fostering and comprehension-monitoring activites. Cognition and instruction, 2, 117-175.

Patel, A. D. (2007). Music, Language, and the Brain. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Peretz, I., Cummings, S., & Dubé, M. (2007). The Genetics of Congenital Amusia (Tone Deafness): A Family-Aggregation Study. The American Journal of Human Genetics, 81, 582-588.

Peretz, I., Brattico, E., Jävenpää, & Tervaniemi, M. (2009). The amusic brain: in tune, out of key, and unaware. Brain: A Journal of Neurology, 132, 1277-1286.

Piaget, J. (1954). The construction of reality in the child. New York: Basic Books.

Reimer B (2003). A philosophy of music education: advancing the vision, 3rd edn. Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ.

Rogers, C. (1969). Freedom to learn. Columbus, OH: Charles E. Merrill.

Rosen, C. (2000). The aesthetics of stage fright. In, Critical Entertainments: Music old and new (7-11). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Sacks, O. (2007). Musicophillia: Tales of music and the brain. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Saffran, J. R. (2003). Musical learning and language development. Annals of the New York Academy of Science, 999, 397-401.

Shively, J. (2002). Constructing musical understandings. In: Hanley, Betty and Goolsby, Thomas W. (Eds.), Musical understanding: Perspectives in theory and practice (201-214). The Canadian Music Educators Association.

Sternberg, R. J., & Lubart, T. I. (1999). The concept of creativity: Prospects and paradigms. In: Sternberg, R. J., (Ed.), Handbook of Creativity, (3-15). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Strand, Katherine. (2011). A Socratic dialogue with Libby Larsen: On music, musical experience in American culture, and music education. Philosophy of Music Education Review, 19(1), 52-66.

Strand, Katherine. (2006). Survey of Indiana music teachers on using composition in the classroom. Journal of Research in Music Education. 54(2), 154-167.

Stravinsky, Igor. (1970). Poetics of music in the form of six lessons. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Swanwick, K., & Tillman, J. (1986). The sequence of musical development: A study of children’s composition. British Journal of Music Education, 3, 305-339.

Upitis, R. (1992). Can I play you my song? The compositions and invented notations of children. Portsmouth, N. H.: Heinemann.

Webster, P. (2002). Creative thinking in music: advancing a model. In: T. Sullivan and L. Willingham, (Eds), Creativity and music education (16–33). Canadian Music Educators’ Association, Edmonton, AB.

Webster, P. (2013). Children as creative thinkers in music: Focus on composition. In: McPherson, G. E., and Graham, F. W. (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Music Education, Vol. 1 (421-428). New York: Oxford University Press.

Wehr-Flowers, E. (2006). Differences between Male and Female Students’ Confidence, Anxiety, and Attitude toward Learning Jazz Improvisation. Journal of Research in Music Education, 54(4) 337-349.

Wiggins, J. (1996). A frame for understanding children’s compositional processes. In: Hickey, M. (Ed.), Why and how to teach music composition: A new horizon for music education. Reston, VA: MENC: The National Association for Music Education

Wiggins, Jackie. (1999). Control and creativity. Music Educators Journal, 85(5), 30-35+44.

Wiggins, J. (1999/2000). The nature of shared musical understanding and its role in empowering independent musical thinking. Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education, no. 143, 66-90.

Wiggins, J. (2009). Teaching for musical understanding (2nd ed.) Rochester, MI: CARMU, Oakland University.

Wiggins, J. & Espeland. (2013). Creating in music learning contexts. In: McPherson, G. E., and Graham, F. W. (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Music Education, Vol. 1 (341-360). New York: Oxford University Press.

Williams, David. (2011). The elephant in the room. Music Educators Journal, 98(1), 51-57.

Wilson, C. C. (2003). The national standards for music education: Awareness of, and attitudes towards, by secondary music educators in Missouri. Missouri Journal of Research in Music Education, Kansas City, MO: University of Missouri, 40, 16-33.

Yoo, S., Lee, C., & Choi, B. (2001). Human brain mapping of auditory imagery: Event-related functional MRI study. NeuroReport, 12, 3045-3049.

Younker, Betty Anne. (1996). The nature of feedback in a community of composing. In: Hickey, M. (Ed.), Why and how to teach music composition: A new horizon for music education (233-242). Reston, VA: MENC: The National Association for Music Education

Zatorre, R. J., Halpern, A. R., Perry, D., Meyer, E., & Evans, A. (1996). Hearing in the mind’s ear: A PET investigation of musical imagery and perception. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 8(1), 29-46.

Zatorre, R. J., & McGill, J. (2005). Music, the food of neuroscience? Nature, 434(7031), 312-315.