Shrinking the Director: Reconceptualizing Ensembles in Undergraduate Music Education

Brian N. Weidner, Butler University

An ongoing discussion in instrumental music education is what the role of traditional large ensembles should be given the changing nature of general education and the place of music within contemporary society. Kratus (2007) summarized his concerns about the large ensemble in two statements: “music education has become disconnected with the prevailing culture” (p. 44) and “the teaching model most emulated in secondary ensembles is that of the autocratic, professional conductor of the large, classical ensemble” (p. 45). Similarly, Williams (2011) outlined many of the problems with the large ensemble including its large class sizes, lack of student-centered learning and creative decision-making, narrowly defined musical styles, reliance on traditional notation and instrumentation, and high expectations for initial entry and functional mastery. He advised that changes be implemented that moved music education away from traditional ensembles in favor of “starting over completely with different types of music experiences for students” (p. 57).

Others have advocated for a less dramatic departure, focusing instead on “emphasizing innovative approaches for curricular change from within the system rather than by advocating tearing the system down” (Miksza, 2013, p. 48). Miksza’s recommendations for reforming ensemble music education included increased breadth and depth of comprehensive musicianship experiences, collaborative music-making, and inclusive repertoire. Others have recommended sharing responsibilities with students throughout the rehearsal process (Morrison & Demorest, 2012), emphasizing participatory music-making and concepts of equality, cooperation, and conflict (Tan, 2014), and problematizing the ensemble space by emphasizing the critical role of conductor as educator (Allsup & Benedict, 2008).

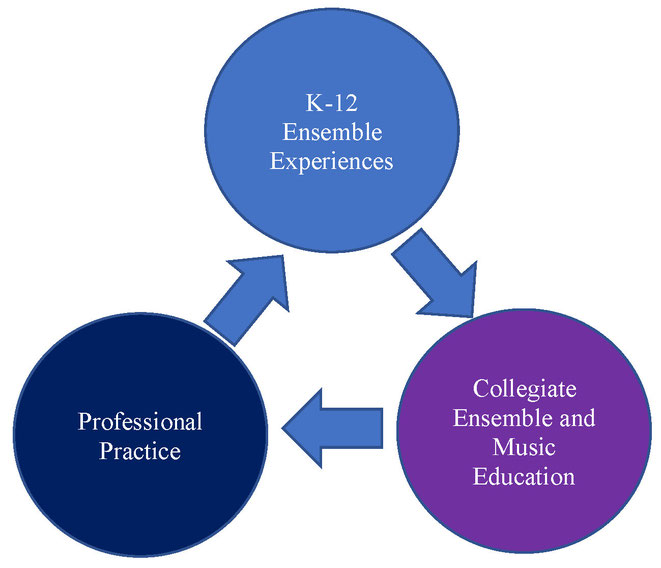

One issue with reforming large ensemble practices is that most music educators have never experienced these practices in their own musical development. As stated by Allsup and Benedict (2008), the problems with the American wind band “stem from an inheritance that is overwhelmed by tradition, an episteme that represents its success in terms that are very familiar to the spirit of American competitiveness, efficiency, exceptionalism, and means-ends pragmatism” (p. 157). In short, and applicable to all traditional ensembles, we teach as we were taught in a canon-focused, director-centric mode. As seen in Figure 1, music experiences for most current music educators were director-centric and built around a limited range of experiences through the end of high school. Even when entering collegiate study, ensembles were performance-centered and led by a dominant conductor who dictated decisions. Coursework associated with creativity, student initiative, popular music styles, and other suggested reforms were often kept separate from the traditional ensemble or left to the purview of general music methods. It is of little surprise that after experiences that have emphasized the historical tradition of the large ensemble that most music educators teach from that same orientation.

Figure 1. Self-replication cycle of music ensemble tradition

To create future classrooms that are primed for forward-thinking reform, it is imperative that this cycle of tradition be interrupted. I have personally observed large ensemble classrooms in which this sort of disruption has occurred (Weidner, 2018). In these schools, student voice was brought to the forefront and rehearsals were managed collaboratively by teacher and students. An emphasis was placed on music-making both within and outside of the classroom through musicianship of various types away from the large ensemble.

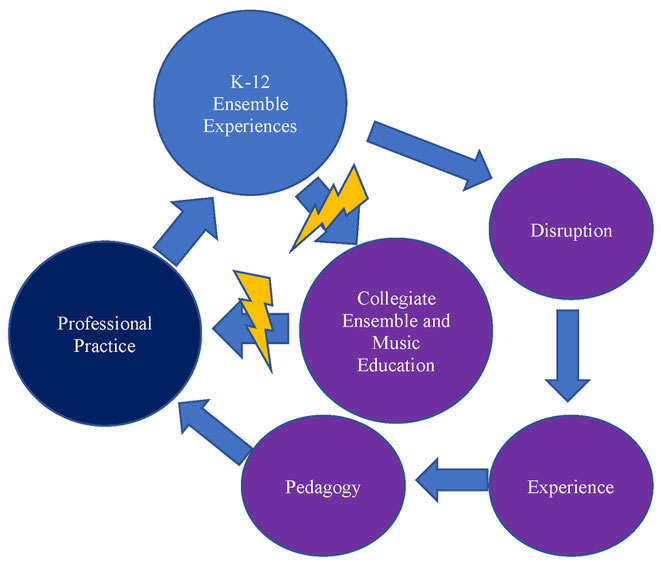

Unfortunately, most of our future music educators have not had these experiences prior to collegiate study, so it is imperative that we provide these experiences for them as part of their undergraduate experience. In order to prepare them for innovative practices in their own classrooms, music teacher educators need to include curriculum that disrupts this cycle, provides meaningful experiences in alterative formats of ensemble music-making, and establishes pedagogy for teaching in a more inclusive, student-centered fashion, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Breaking the self-replication cycle of music ensemble tradition

At Butler University during the 2018-2019 academic year, I instituted a curriculum that created this sort of disruption in my students’ music education. While these changes are still not fully realized across the curriculum, what follows provides an example of what this interruption could look like within three required courses: Brass Techniques, the Butler University Symphonic Band, and Comprehensive Instrumental Techniques. In addition to the described reforms, these courses include traditional practices, suggesting that being innovative in the classroom can be a compliment to ensemble traditions.

Disruption

At the sophomore level, Brass Techniques focused on learning technical performance and pedagogical practices associated with brass instruments and met twice a week in a 50-minute session. Notably, there was no pre-determined curricular approach for this two-semester sequence of courses for Butler’s sophomore music education students prior to the 2018-2019 academic year. While this course had traditionally been taught using a method book approach focusing on developing individual proficiency, I presented the two semesters of the course as a disruption to the students’ previous experiences by emphasizing frequent informal performances, creative activities, aural practices, and student-led music-making.

During the first semester of the course, students rotated through trumpet, horn, trombone, and euphonium in heterogenous groups, with approximately three and a half weeks on each instrument. The goal was to introduce transferable fundamentals of brass playing and provide a cursory introduction to the unique aspects of each instrument. With each instrument rotation, we approached introductions to instruments using a different pedagogical approach. The first rotation was entirely aurally-based with a focus on tone production, imitation, and creativity, despite students’ limited technical ability. The second rotation centered around improvisation and short activities in composition, again in an aurally-based setting where students engaged extensively in call-and-response, drone activities, and exploratory music-making. The third rotation served as a critique of method book-based approaches, where each student was assigned one of a half-dozen common band method books to teach one another from, with an emphasis on evaluation and manipulation of method book materials and incorporating aural skills and creativity into existing texts. The final rotation was the only one which was strongly based in notated music, as the students taught one another their previously learned brass instruments utilizing excerpts from band and orchestral literature as the foundation for their instruction.

Throughout all stages, students were actively teaching. Initially, they taught their peers in the class through problem diagnosis and correction activities. By mid-semester, students found non-brass playing peers to whom to teach beginning lessons. The semester concluded with visits to area middle schools where my students taught beginning students. All teaching activities used aurally-based methods, disrupting the model of beginning instrument instruction based in method books to which my students were accustom from their own experiences.

The second semester of the course focused more heavily on a participatory model of instruction with performances every two to three weeks. During each cycle leading up to these performances, the students were the primary teachers of the class, and the emphasis was upon constant engagement of all students and meaningful participatory performances. There was no predetermined set of skills that were to be developed; rather, the music the students chose to perform dictated the skills they needed, matching the model of emergent music-making that Green (2008) espoused in her popular music pedagogy. Throughout the semester, the students focused on practices for chamber ensembles, Mexican mariachi and banda, jazz combos, and popular music-making. Each cycle ended with a performance to other instrument techniques courses, the weekly School of Music colloquium (as seen in Video 1), or passersby in the lobby of the building.

My emphasis this semester was less upon developing brass techniques as it was upon using brass instruments as a means for participatory music-making; brass learning was effective yet incidental. The students were told at the beginning of the semester that the goal by the end of term was that they had developed a secondary instrument that they could perform at an intermediate level. From there, they were allowed to choose which brass instruments they wished to focus on and the music they wished to study within broad genre parameters. Some selected to stay with a single instrument throughout the semester, while others rotated with each new performance cycle. The goal throughout was to develop the instrument as a means of performance, as opposed to meeting a fixed set of skill competencies.

Within each cycle, the students were primarily responsible for their own musical progress. They selected the literature performed, planned their in-class rehearsals, and guided their own music-making. As the instructor, I observed and mediated these sessions, helping to shape pedagogical approaches to small group, student-led instruction. These student-led sessions were augmented by whole class discussions about effective practice, approaches for overcoming particular challenges, and introductions to musical genres with which students might not be familiar. The goal of these experiences was to disrupt the students’ perspectives of what beginning instrument instruction is and could be through multiple experiences in something different than what they had previously experienced.

Video 1: Popular music pedagogy performance at School of Music colloquium

Experience

The second stage of breaking the self-replication cycle was providing sustained experiences in alternative approaches to the ensemble. This occurred during the 2018-2019 academic year in the Symphonic Band, which was the second band at Butler University and was evenly divided between music majors and non-majors. Throughout the academic year, we used a model of collaborative music-making including discursive practices, student questioning, and open rehearsal planning. The central sustained experience was one piece per concert cycle utilizing a conductor-less model. During these experiences, students were tasked with making all the decisions from first rehearsal through final performance without the ensemble director’s direct engagement.

I started this conductor-less experience with a video introduction to the conductor-less ensemble model (Orpheus Chamber Orchestra, 2016) and a brief discussion of my expectations for the group. These expectations were simple in theory. First, the ensemble members would be responsible for all rehearsal planning and execution within the time constraints provided by the directors. Second, they would be performing the piece on the next concert. For the sake of expediency, my co-director and I selected the pieces used and established the time allocated for rehearsal of the piece. At this point, students assumed all rehearsal responsibilities for the pieces. All students had electronic copies of the entire scores, professional recordings, and rehearsal recordings to consult in rehearsal and score study, housed within our classroom management system. On occasion, my co-director or I stepped in with a guiding question or was asked a question by a member of the ensemble, but we largely remained off to the side observing the process, managing the rehearsal recording, and adjusting the projected score if requested by ensemble members. At the end of each rehearsal, I facilitated a brief discussion reflecting on what worked (or did not) in the rehearsal and setting goals for the next rehearsal.

At first, these rehearsals were very disorganized, dominated by repetitions of large sections of the music, typically starting at the beginning of the piece. There was little strategy usage of any sort, and transitions between playing activities took a long time as students talked around their musical issues. Quickly, individuals rose to be leaders in the rehearsal, dictating most of the decisions and facilitating quicker transitions between rehearsal segments. This rise of individual leaders also bred resentment from other students as they felt that a small number of students had hijacked the rehearsal. This led to a discussion about the need for the entire group to contribute to the process.

By the fourth rehearsal using the conductor-less model, the nature of rehearsal had changed greatly. A hierarchy had developed in which members of the ensemble “telephoned” their concerns to a group of leaders who coordinated the rehearsal. Students began to start the rehearsal with a short planning session to set priorities and details for rehearsal. Eventually, this planning session changed to the end of the previous rehearsal, allowing students to better plan for subsequent rehearsals. Rehearsals became increasingly deliberate and focused, with short sections being rehearsed using a broader range of approaches with a great deal of corrective criticism, as can be seen in Video 2. Rather than rehearsing large sections, participants stopped rehearsal immediately if things did not go as planned.

In interviews following rehearsals, the participants commented on the impact of this experience on their music-making. While some resented the experience stating, “I come to band to be told by an expert [the directors] how to make music so that I can learn how to make music better,” others noted that it made them “more aware of what and how music should be made.” Several commented that this was the first time in their musical careers they were held responsible for music-making in the large ensemble, and that this experience “made them think about all the music they played.” This was evident in one particular rehearsal, immediately after an 11-day Thanksgiving break. The rehearsal had gone extremely poorly on three director-conducted pieces, to the point that we were considering removing a piece with a concert a week away. 15 minutes had been allocated for our conductor-less piece, Anne McGinty’s Twas in the Moon of Wintertime, which became the turning point in the rehearsal. Following this piece, the rest of the rehearsal was highly productive, focused, and musical. When the participants were asked what they felt contributed to this pivot, several stated that the accountability for making music that came with the conductor-less piece reminded them that “no one is going to make music except for us.” This experience not only influenced the piece it was used on but also the students’ overall approach to music-making, helping them to recognize their role in critically thinking about the rehearsal.

Video 2: Conductor-less ensemble rehearsal in the Symphonic Band

Pedagogy

For future music educators, it is critical that the students are explicitly taught how to bring student-led, egalitarian practices into their own classrooms. Like many programs, our junior students had extended practicums in local schools in which they work with 6-12 students on a regular basis as part of our Comprehensive Instrument Techniques course. In addition to more traditional pedagogies, this course also focused on the inclusion of three student-centered approaches, specifically Socratic questioning, student decision-making, and critical goal setting.

The purpose of teaching Socratic questioning was ensuring that future educators could pose questions in a way that required conscious thought by their students and progress from vague to specific. This form of questioning focused on engaging in deep questioning with open-ended possibilities as opposed to surface level inquiries that led to a single answer. I incorporated the development of question sequences as part of my students’ lesson planning activities to teach them how to ask meaningful questions of their students. When these pre-service teachers headed into classrooms to work with students, they practiced asking questions with wait time that expected their students to think critically and answer problems themselves.

By teaching with Socratic questions, pre-service teachers were able to provide opportunities for their students to make decisions that matter. As recommended by Allsup and Benedict (2008) and Morrison and Demorest (2012), we discussed how to relinquish control as the teacher and share decision-making responsibilities with students. While Socratic questioning came quickly to pre-service teachers as they have used it outside of music, sharing decision-making responsibilities regarding what and how to rehearse was a challenge, as they had seldom seen this in their own ensemble experiences. I began this shared decision-making as an extension of Socratic questioning by having pre-service teachers ask their practicum students for recommendations of how to best work on a problem or identify a difficulty they were encountering. The most difficult element for my students was allowing their students’ decisions to matter in the way that rehearsal was executed from there.

The third key concept taught in methods coursework was teaching practices for student-led goal-setting, which grew out of student decision-making. Within the methods course, we discussed it as both initiating and closure activities. Group goal-setting served two functions. First, it ensured that the preservice teachers and their students had an agreed upon idea of where they intended rehearsal to head. Second, it invited their students to make critical decisions about their learning. The key instructional component within our methods course to incorporate goal-setting in preservice teachers’ practices was the inclusion of initiating and concluding activities within every submitted lesson plan. Our pre-service students were expected to engage their students critically in the opening and closing activities, leading to active goal-setting and evaluation by their students.

Conclusion

My core argument here is not that we supplant traditional rehearsal and instructional methods with those which promote egalitarian practices. Rather, my suggestion is that disruptive experiences are included alongside traditional practices within undergraduate education to provide students and future educators with alternatives to director-centric large ensembles. Once these disruptive experiences have been introduced and sustained as part of undergraduate music education, preservice educators are prepared to incorporate these alternative practices into their own pedagogy in practicums and their future professional classrooms. Only by disrupting the cycle of director-centric large ensembles will we create a new cycle of egalitarian K-12 experiences that lead to empowered undergraduate students who will become student action-focused educators.

References

Allsup, R. E., & Benedict, C. (2008). The problems of band: An inquiry into the future of instrumental music education. Philosophy of Music Education Review, 16, 156-173. doi://10.2979/pme.2008.16.2.156

Green, L. (2008). Music, informal learning, and the school: A new classroom pedagogy. Burlington, VT: Ashgate.

Kratus, J. (2007). Music education at the tipping point. Music Educators Journal, 94(2), 42-48. doi://10.1177/00274310709400209

Miksza, P. (2013). The future of music education: Continuing the dialogue about curricular reform. Music Educators Journal, 99(4), 45-50. doi://10.1177/0027432113476305

Morrison, S. J., & Demorest, S. M. (2012). Once from the top: Reframing the role of the conductor in ensemble teaching. In G. E. McPherson & G. R. Welch (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of music education. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Orpheus Chamber Orchestra. (2016, May 12). The Orpheus Process [video file]. Retrieved at https://youtu.be/OLdfjYT_LFI

Tan, L. (2014). Towards a transcultural theory of democracy for instrumental music education. Philosophy of Music Education Review, 22, 61-77. doi://10.2979/philmuseducrevi.22.1.61

Weidner, B. N. (2018). Musical independence in the large ensemble classroom. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuest (#10822082).

Williams, D. A. (2011). The elephant in the room. Music Educators Journal, 98(1), 51-57. doi://10.1177/0027432111415538